In our regular hacksession, the current season ;), we are focusing on threading.

Concurrency/Multithreading is a really hard topic it has a lot of very specific nomenclature and there are different 'levels' of concurrency one might say.

I will start with the nomenclature starting from the programmers / OS perspective.

Process and thread

We have Processes and we have threads.

A process is a model of running software on an OS with isolated memory. The data - if intended and from the userland perspective - is only accessible via defined a API / ABI.

A thread or 'thread of execution' is a way to run/execute parts of a software which can - if intended - access shared memory provided by the parent process who spawned the threads.

In rust every process has a main thread which can be accessed via:

use std::thread;

use std::time::Duration;

fn main() {

let main_thread_handle = thread::current();

}

This means have processes which are started by the OS that spawn threads which can be handled by the OS or a given runtime.

A process can spawn as many threads as it needs (within OS limitations) and the threads have theoretical access to the memory allocated by the OS for the process.

Since the allocation, virtualization and coordination of resources is more costly for an OS than just coordination of resources, a thread can be seen as cheap in comparison to a process from an OS perspective.

But a thread is still more costly than no thread. Which also could mean going full on parallel can be slower than being single threaded in specific cases.

Process definition from wikipedia:

- processes are typically independent, while threads exist as subsets of a process

- processes carry considerably more state information than threads, whereas multiple threads within a process share process state as well as memory and other resources

- processes have separate address spaces, whereas threads share their address space

- processes interact only through system-provided inter-process communication mechanisms

- context switching between threads in the same process is typically faster than context switching between processes.

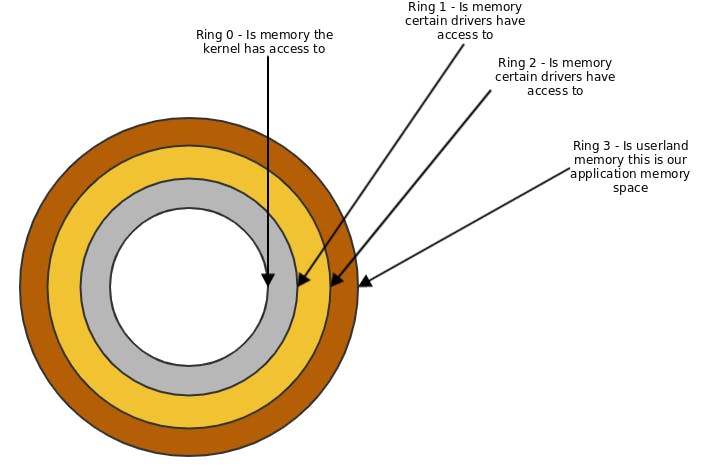

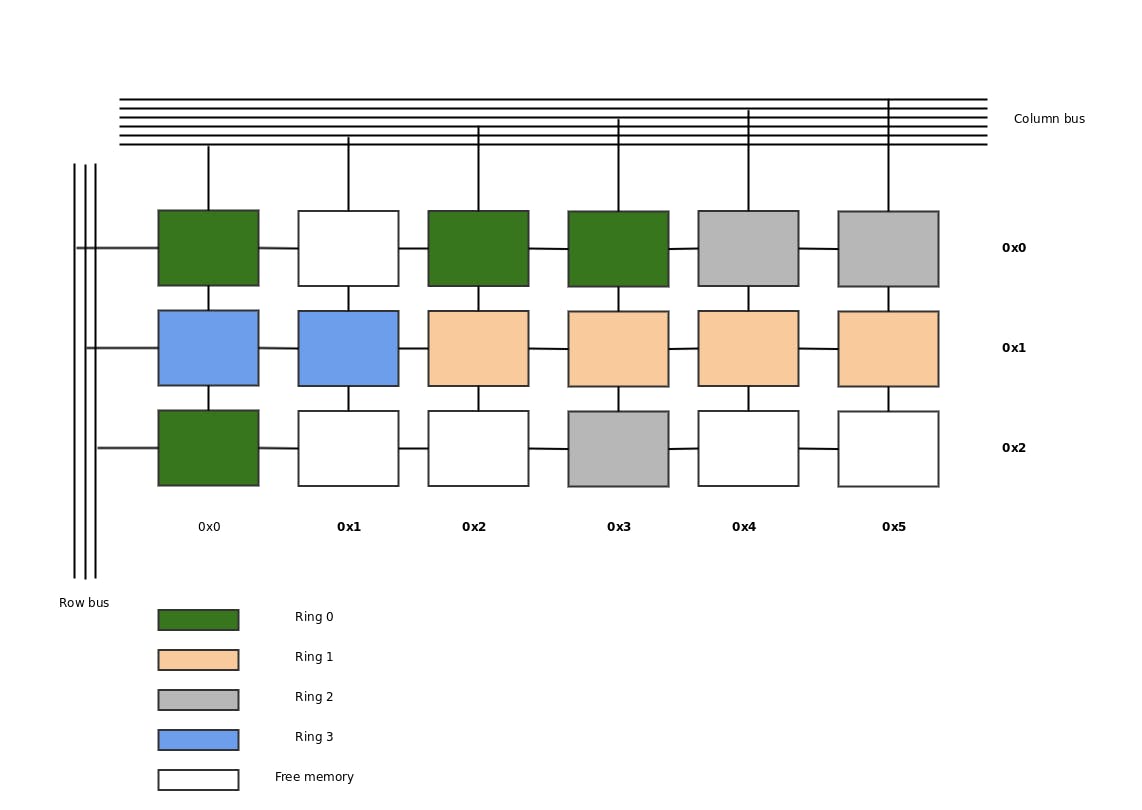

Lets take a short detour to the ring model of OS memory:

Ring model

The ring model describes an access permission system not a space dimension.

Also there are negative rings that are built for HSM (high security modules) and have an extra layer of protection even the kernel should not access.

But for 'simplicity' sake we will start with ring 0 which is where our OS-Kernel is running and has full control over.

The rings define a privilege hierachy where the direction are privileges is inside out. For example ring 0 can access ring 1 but not the other way around.

Why is this important? Well those protective rings also provide access to certain CPU instructions and this can be important. Also I believe it's important to understand the different concepts to understand how systems work.

Also observability is a big factor within concurrency and if processes are running in different rings at least from an OS perspective can make a huge difference.

For more information about rings

A 'more' realistic memory mapping would be along the line of this:

In reality we're talking about managing addresses, addresses can be seen as bit patterns where the OS allows access to certain addresses, or not.

Our kernel can access all the addresses in our model and it provides the needed addresses for our drivers and programs.

As you can see the addresses based on the rings don't need to be aligned in the address-space, it can but it's not a necessity.

Memory Virtualization

Another trick comes into place from our program/application view. Address virtualization.

Our OS will create a mapping table of addresses to simulate our program that it's alone. So for example every program might think it works with the memory addresses 0x1 to Fx1 when in reality the addresses are translated via a virtualization table to the real hardware addresses of our OS.

The same goes for hybrid-virtualizations like virtualbox. The Hypervisor will lie to our VM and tell it, that's it's the only one on the system and translate the memory and CPU time.

From our process perspective and our thread perspective we own all the memory there is. meanwhile our process has no clue how much memory really exists outside of information provided by the OS.

Process from an OS Perspective as an allegoric idea

- System call to the OS 'hey start this'

- OS registers address of starting point of the program in execution pages

- OS tries to accommodate request for memory

- OS loops over running processes and schedules execution time

- OS listens for interrupts / sys calls

- OS registers possible threads

- OS provides access to certain memory spaces if for example a network package comes in and the program is allows to access it

- OS schedules our CPU time and tries to balance it with the other running programs.

What is an OS?

An OS is a piece of software that runs and administrates other software and hardware.

A bit vague? To me it's a rather good description without impediments of implementation and usecase intentions.

If we look at the most basic/primitive implementation of an OS is a program running in an endless loop sending no-op instructions.

A modern OS implementation however needs to do more

- Security

- Control over system performance

- Job Scheduling

- Error detection aid

- Coordination between other software and users

- Memory management

- Processor management

- Device management

- File management

An OS can be seen as a big resource management system that provides and manages them for us.

Basics of a CPU

Physics

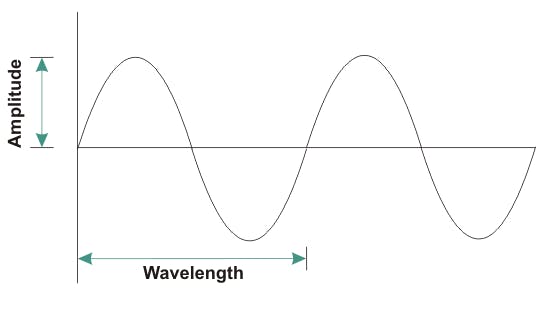

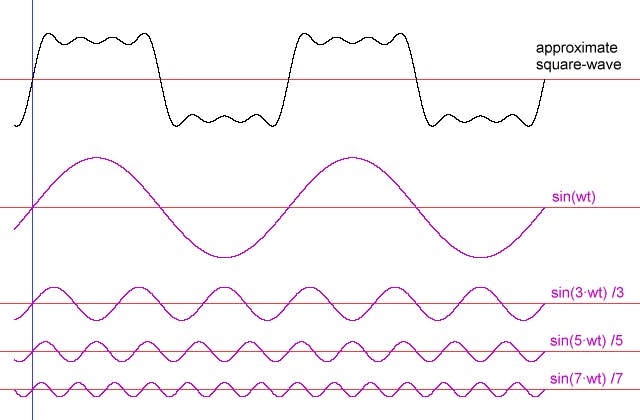

Why an endless loop? and no waiting? Due to the nature of our hardware. The CPU runs on an electric wave which is transported via the FSB where every voltage peak (U) or absence of it, within a given interval (Hz) that reaches a certain threshold is seen a 1 or 0 (digitalization) values.

This is also known as clock cycles. So 1 interval with or without a peak of electric potential.

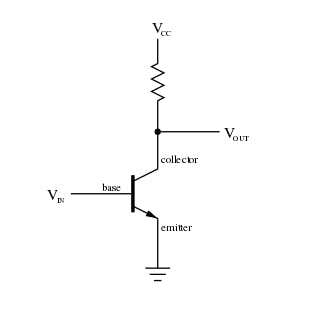

This wave will be translated via transistors

into a digital signal

A transistor usually is built out of a semiconductor although there have bin new experiments with graphene. In general a transistor can be seen as a switch that flips if a certain Voltage/Potential (U) is reached.

This due to the gap of semiconductor which allows the transfer of electrons from the valence band to the conducting band.

You can simplify it by imagining that by increasing the voltage you push the bands closer together and make it easier for the electrons to 'jump' across the gap between the bands.

Our CPU gets a stream of instructions that can be 0 and 1 or not enough potential and enough potential.

Which is not enough to actually do anything, you can stay in your room and flip on and off your light it has no meaning without context.

the context is as so often time. So we have a clock that oscillates in a certain rhythm which allows us to actually define a unit of information over time which we like to call bits.

This means our CPU always is working, our whole system has an internal clock and if we don't provide the CPU anything to do it will still work as long as it's turned on - rather little since it has builtin logic gates to reduce energy waste.

This is core nature of a CPU it always runs. Or is it? ... that's an interesting question posed by alan turing the so called halting problem

Which we wont touch at the moment.

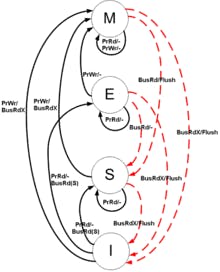

CPU - MESI

We need to understand that concurrency and parallel computing crosses boundaries between our program, the OS and the CPU or any other form of distributed 'processor'.

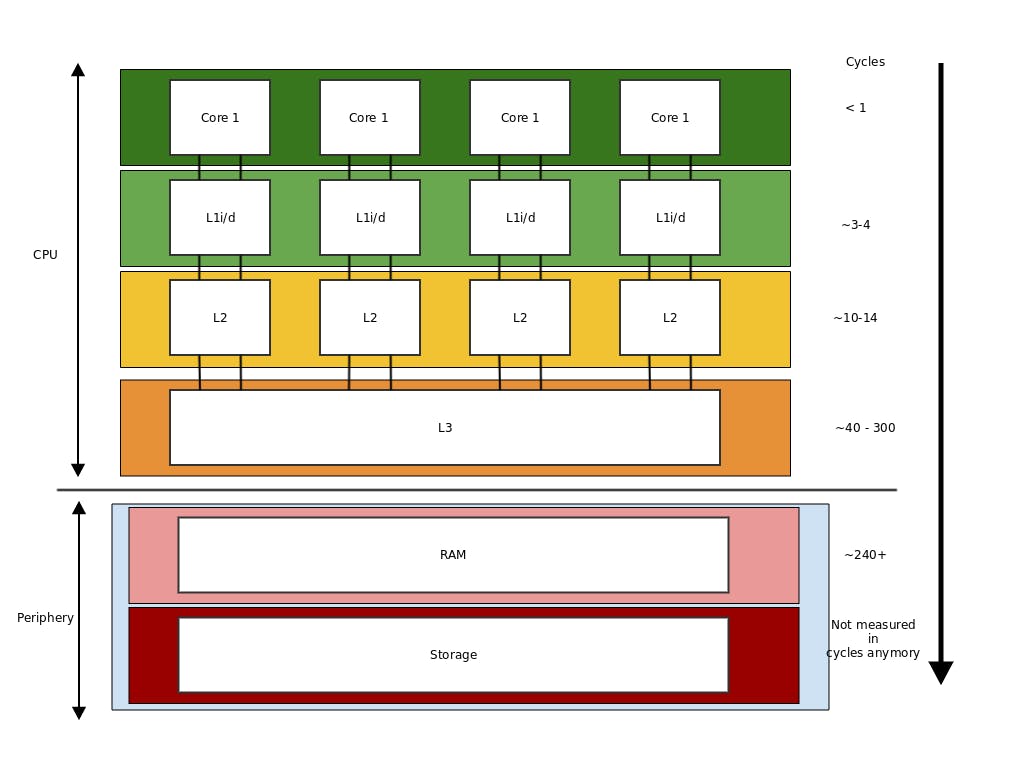

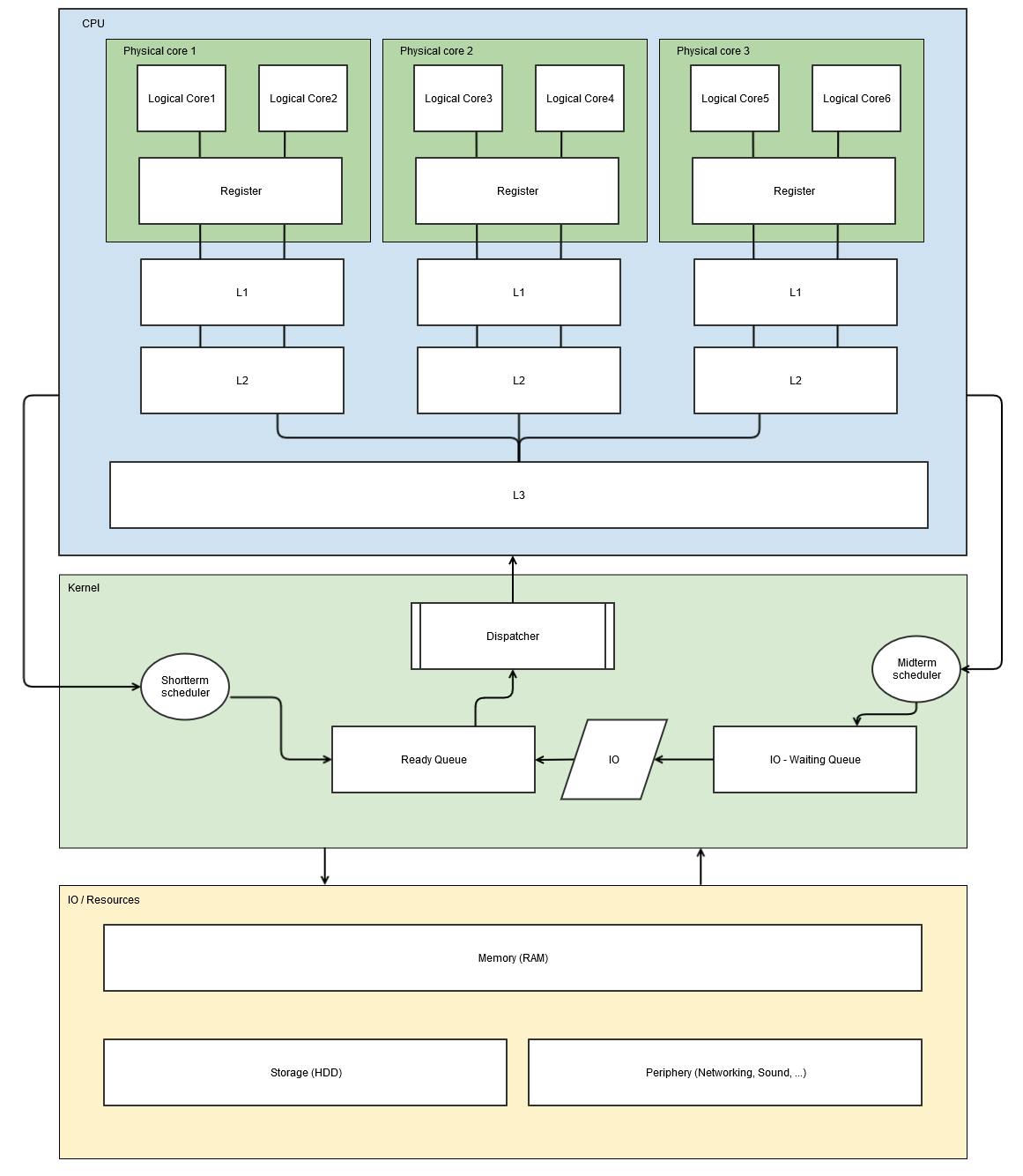

Our modern CPU architecture is built out of multiple components

for a little more information about timescales and computer latency at a human scale

A short disclaimer, the numbers are architecture specific so please just look at them as baselines not as laws of nature.

The usual task of an CPU is as follows

- fetch information

- process information

- store information

This is what every CPU does, it's in the name, central processing unit.

But how do the cores work? and how do the registers and cache work? and why is this even relevant?

Well. If there is only 1 core in the CPU it's not. As soon as we have multiple cores that should work on the same problems the cooperation problem starts.

How do we coordinate the flow of data between different cores? We know we want it to be fast! so we try to fill the lower caches with the information needed if possible.

But what if Processor 1 does the first part and processor two does the second part? if we look at the diagram we see that the L1 and L2 caches are not shared.

How do can we efficiently communicate between our CPUs to ease some of the problems any distributed system has.

MESI to the rescue.

MESI is a statemachine that has 4 core states

- Modified (hey this has been changed)

- Exclusive (hey I am going to change this)

- Shared (everyone can read this)

- Invalid (Hey this has been changed, it's not valid anymore)

This allows an inter-cache distribution and communication! It allows the cores to get information from the other caches.

And If you think about rust again and how ownership works, to me this get's really close on an abstract idea of computation

- you need to own it to write (exclusive)

- you can share for read it as long (shared)

- the modified and invalid are prohibited in the model since you either have to ARC it or RC it with atomics or constructs like mutex.

But the core idea of exclusive write and shared read is something I do enjoy about that language a lot.

Branch Prediction

Branch prediction is the attempt of the branch-predictor

to guess the possible outcome of an instruction branch before actually computing it using the "idle" cycles of a CPU to fetch the data needed and speculative execute it.

Since the cost of a miss is as costly as doing nothing this system increases the efficiency of the throughput of the given CPU.

Well more about the risk and benefits can be seen in spectre, meltdown, MDS attacks...

Hyperthreading

Hyper-threading is the technique developed by Intel where every physical core is separated into two logical cores by duplicating the architectural state within a physical core.

So the current execution state is persisted but not the data state. So the logical core can be interrupted and still know his execution state which in term allows the OS to see this virtual core as real core.

Lets get back to the rust threading

Greenthreads

Greenthreading is the technique called where the scheduling of threads are moved out of the kernel space into the userspace to reduce the overhead of spawning a thread from the kernel

Which means even "cheaper" threads but also means a runtime which is why it was kicked out of rust at the time. Because of zero cost abstractions.

This has a certain advantage for example it can utilize futex sys calls and the problem of a balanced execution tree like the OS is not needed.

An OS will always try to be 'fair' and distribute the workload greenthreading allows you to basically spawn N threads and still just use 1 because efficiency is a question of perspective and intent.

1. basic thread spawning

use std::thread;

fn main() {

case1();

}

fn case1() {

let t1 = thread::spawn(|| {

println!("Thread 1");

});

let t2 = thread::spawn(|| {

println!("Thread 2");

});

let t3 = thread::spawn(|| {

println!("Thread 3");

});

// needed otherwise it does not block till

// the threads actually have been run

t1.join();

t2.join();

t3.join();

}

this basically just spawns 3 threads. since there is no guarantee for the order of execution of threads we most likely get the result as expected but we need to wait at the end to make sure our main thread that contains our other 3 threads does not terminate before we see our println! in action

builder

// example from the rust book

fn main() {

let child1_thread = thread::Builder::new()

.name("child1".to_string())

// in mebibyte MiB designed to replace the megabyte

// when used in the binary sense to

// mean 2^20 bytes, which conflicts with

// the definition of the prefix mega

.stack_size(1) // default is 2

.spawn(move || {

println!("Hello, world!");

});

}

this is for naming also the stacksize can be defined. I can imagine there are usecases for this, but I am guessing that most of us won't use it that often.

Sleeping in threads

fn main() {

let t1 = thread::spawn(|| {

thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(2));

println!("Thread 1");

});

let t2 = thread::spawn(|| {

println!("Thread 2");

});

let t3 = thread::spawn(|| {

println!("Thread 3");

});

t1.join();

t2.join();

t3.join();

}

This is something pretty common in most languages we can add a sleep command and wait for a certain amount of time. This can get interesting for time and consistency windows. or just to reduce the load.

thread local storage

fn main() {

use std::cell::RefCell;

// create a local store

thread_local! {

pub static THREAD_LOCAL_VALUE: RefCell<u32> = RefCell::new(23);

}

THREAD_LOCAL_VALUE.with(|value| {

*value.borrow_mut() = 3;

});

let t1 = thread::spawn(|| {

THREAD_LOCAL_VALUE.with(|value| {

*value.borrow_mut() = 12;

});

});

t1.join().unwrap();

THREAD_LOCAL_VALUE.with(|value| {

println!("{}", *value.borrow());

})

}

as we can see we're using a RefCell. A RefCell is not threadsafe! What this does is creating a thread localized value storeage that can be accessed within every thread without ownership problems.

The value also remains localized so thread0 cannot access the value of thread1 for example.

Parking a thread

fn main() {

let t1 = thread::spawn(|| {

println!("park thread");

thread::park();

println!("unpark");

});

thread::sleep(Duration::from_secs(2));

t1.thread().unpark();

t1.join();

}

We can park a thread and resume waiting lateron. This article is already pretty long so I will skip the parts where we would look in the sys calls and see what's actually happening on my system.

Threads with Atomic bool

fn main() {

let atomic_lock = Arc::new(AtomicBool::new(true));

let atomic_lock2 = atomic_lock.clone();

let t1 = thread::spawn(move|| {

atomic_lock2.store(true, Ordering::SeqCst);

});

t1.join();

println!("{}", atomic_lock.load(Ordering::SeqCst));

}

So lets look at this a little more in detail. we create an atomic boolean and put it in the Arc.

What is an Arc? Arc is the threadsafe reference counter / smart pointer that points to our value. To actually use something across threads we need to avoid ownership problems.

if we would just use

let atomic_lock = Arc::new(AtomicBool::new(true));

and apply

let t1 = thread::spawn(move|| {

atomic_lock.store(true, Ordering::SeqCst);

});

we would transfer the ownership via the code-word move to the thread.

so we need to invoke clone on it.

let atomic_lock2 = atomic_lock.clone();

this increases the reference counter to two and we can pass our second reference to our value safely to the thread. and let our main thread (fn main) share the state with our extra thread (thread::spawn).

atomic_lock.store(true, Ordering::SeqCst);

Now we're getting to the part why the CPU and memory model can be useful.

Atomics and ordering

Atomics in rust implement the LLVM fences

- Relaxed

- Release

- Acquire

- AcqRel

- SeqCst

They not only define the behaviour of the atomic, but also of the !!surrounding code!!. This means that guarantees about the order of the code execution between threads can be very different from what we expect

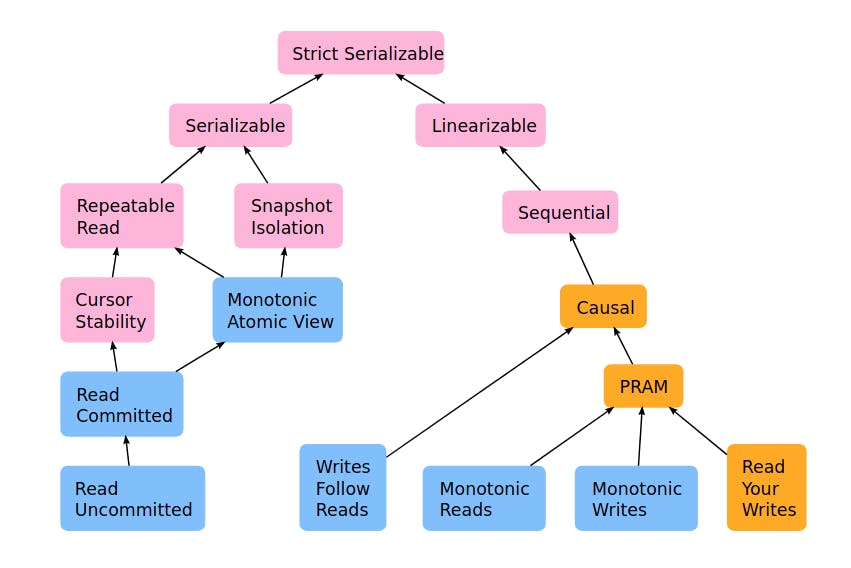

As soon as we move into "multithread" land we have to understand that we're actually need to think similar to a common distributed system model, with a likely lower latency.

The more cores you got the more different systems and storages you have. This is what MESI implies. if we got a shared state S in 3 different caches we have no guarantees of order of execution based unless we specifically tell it to the CPU.

That's what Atomic and Fences are for it's a way to enforce an order on instruction level! These are only supported by certain CPUs ofc.

but think about it, based on "state" having 4 cores and 1 RAM has similar problems like having 4 via network connected single cores.

Consistency

SeqCst - Sequential Consistency

Sequential consistency is the default model we want. It does solve a lot of problems and we rarely need to optimize on the instruction level.

So it's save to assume this model will cover 90% of the normal developer cases and we rarely need to move to the other one.

So what does it mean? it means that within all threads the order of execution of the code will remain as we programmed it and we block cache reordering and other optimization steps because we want correctness over efficiency.

Relaxed - Well guess what

Relaxed does what the name implies, it's an atomic that has the least constraints

it is defined as monotonic order. Monotonic is a mathematical term that describes a function that can only move into 1 direction for example an addition within the Set of ℕ.

for example:

- 1+2+1+4+5+1+4+2 is monotonic

- 1+22+24 is monotonic

- 1+-1+2+5 is not monotonic since we 'change' direction by substracting

which means it can !never! return to a former state. so if we can look at our code and it shows this behaviour, relaxed would be a fitting choice. However, most of the time we will write code that does not fit this description so .... an unlikely conscious choice.

For the CPU a monotonic fence just means it does not have to care about the other states that much since they can be moved (MESI - intercache movements) because the instructions within this fence are monotonic.

Aquire, Release and AcqRel

Now we get to something that hopefully really helps understanding what this mean:

Aquire is intended for loads

let x = AtomicUsize::new(0);

let mut result = x.load(Ordering::Acquire);

result += 1;

x.store(result, Ordering::Release); // The value is now 1.

Release is intended for stores they have to be played in order because.

Aquire guarantees that the code that follow it will be in order and Release guarantees that the code that preceeds it will be in order.

So between Aquire and Release the execution order will be maintained.

This means mainly that if you got two threads running different code everything that is happening within Thread A before the acquire is fair game to be 'observed' by Thread B. However to observe things that are happening in Thread A after the acquire lock Thread B also needs an acquire lock.

So for the people who don't understand this and they want more detailed [information about the what.] (medium.com/nearprotocol/rust-parallelism-fo..) this is a really great article about this behaviour.

I will however resume the threading topic with the next construct the mutex.

Mutex

fn main() {

let state = Arc::new(Mutex::new(0));

let shared_state1 = state.clone();

let shared_state2 = state.clone();

let t1 = thread::spawn(move|| {

while *shared_state1.lock().expect("access_state") < 10 {

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(20));

println!("current state {}", shared_state1.lock().expect("access_state"));

}

println!("reached {}", shared_state1.lock().expect("access_state"));

});

let t2 = thread::spawn(move|| {

while *shared_state2.lock().expect("access_state") < 11 {

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(100));

let mut state = shared_state2.lock().expect("access_state");

*state = *state + 1;

}

});

t1.join();

t2.join();

}

What is a mutex? Mutex comes from 'mutual exclusive' and means only 1 thread is allowed to access the values at a time.

this examples basically uses 2 threads. 1 is counting up and the other one is checking the state.

The sleep is only so the program actually shows something besides '10' and exiting ;D

Mutex is one of the most straight forward concepts it's a basic XOR either you or I can have the resource not both of us at a time.

.expect is just my laziness because .unwrap does not give a meaningful response on failure.

RwLock

fn main() {

let state = Arc::new(RwLock::new(0));

let shared_state1 = state.clone();

let shared_state2 = state.clone();

let t1 = thread::spawn(move|| {

while *shared_state1.read().expect("access_state") < 10 {

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(20));

println!("current state {}", shared_state1.read().expect("access_state"));

}

println!("reached {}", shared_state1.read().expect("access_state"));

});

let t2 = thread::spawn(move|| {

while *shared_state2.read().expect("access_state") < 11 {

thread::sleep(Duration::from_millis(100));

let mut state = shared_state2.write().expect("access_state");

*state = *state + 1;

}

});

t1.join();

t2.join();

}

the RW lock essential gives you similar options like mutex one of the core advantages is that readlocks can be shared. So if one thread invokes the read lock, the other threads can too.

Only the write lock can be hold by 1 thread.

I hope at least some of you did enjoy my article, it was quite wild moving through so many topics and I still just scratched the surface because actually I wanted to do some sys calls and see the difference on the OS.

So leave me feedback, corrections and addendums :) I am very curious and always enjoy learning :).

addendum

as Mark was kind enough to mention. RWLocks can have a tendency to 'starve' reads or writes.

What this means 1 thread has a write lock, 10 other threads want a read lock and 2 want a write lock.

Who should be prefered? Is it more important to read? or to write? this is an quite interessting read on this topic.

The question about the hyperthreading model is a bit tricky since hyperthreading needs software to work.

I tried to visualize it accordingly:

The main part, according to the things I read, is done by the dispatcher.

In a superscalar CPU the dispatcher reads instructions from memory and decides which ones can be run in parallel, dispatching each to one of the several execution units contained inside a single CPU. Therefore, a superscalar processor can be envisioned having multiple parallel pipelines, each of which is processing instructions simultaneously from a single instruction thread.

Also for clarification between dispatcher and scheduler geeksforgeeks.org/operating-system-differen.. I recommend taking a look to this.

I hope this makes sense :)

kura🇯🇵 thx :) I replaced the RW code with the correct one.